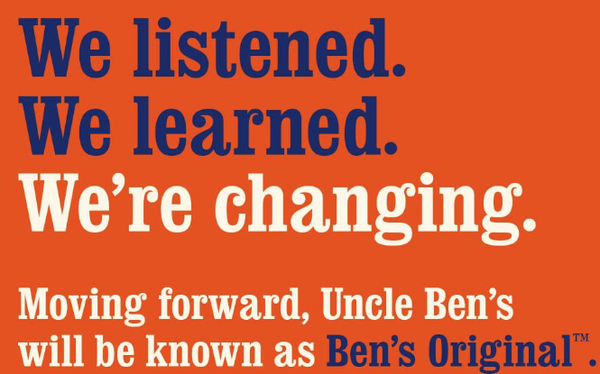

ZEITGEIST UPDATE: I published this on the 3rd. On the 9th, this happened. Time to buy lotto tickets.

As a matter of general principle I try to avoid opening anything I write with as a person of color, but it seems unavoidable here, lest I be accused of taking offense on someone else’s behalf. Let’s talk about Aunt Jemima.

So: In the recent purges of 2020, a number of African-American brand icons have been retracted to satiate the perceived demands of consumers, in the hopes of pre-empting criticism. Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, Cream of Wheat, and some others have been rebranded to more antiseptic versions where the brand iconography is placed at a safer distance from African American history and culture, specifically, African American people. Sometimes this seems obvious, late. At others, I’m not sure why it was necessary.

Far be it from me to want to die on Aunt Jemima hill, but I had the uncanny feeling of loss when Aunt Jemima was canceled, because, well, for a long time you just didn’t encounter that many Black faces on products. The 2020 cancelation was wrongheaded in her case because the necessary upgrade had already happened, when Aunt Jemima was upgraded from her previous incarnation, a mammie-figure, in the 90s. Prior to the 90s there was no doubt, Aunt Jemima was ridiculous, an offensive stereotype, one I instinctively mistrusted even as a child and one my parents refused to buy (we were a Log Cabin family). But after the 90’s rebrand she became just, you know, a lady. She had styled gray hair and looked mature and professional, like maybe she had owned her own agency or something.

It occurred to me that we may be overcorrecting, here, that the solution to not knowing how to best depict Black faces in anything but power positions has become to hide them even when nothing is wrong, that in another attempt at asserting ownership over our image we, well, deleted our image. The kind of hand-wringing that precedes adamantly throwing the baby out with the bathwater, simultaneously overly sensitive and yet, somehow, demeaning. Everybody knows people in power simply don’t sweat this bullshit in the same way: no one ever asked if Betty Crocker or Chef Boyardee were real, or expressed concern about Colonel Sanders’s rank or whether he was practicing Stolen Valor. Colonel Sanders is comfortable in his own skin, has also gone through rebrands, but there is no question that his depiction has only ever been that of “just some guy, possibly a veteran.” In a spectacular feat of historical irony, Aunt Jemima is owned by Quaker, notable abolitionists and decently good sports, where usage of their likeness is concerned.

Now let me specify, for the record, there are a number of good reasons to be suspicious of corporate makeovers, and there can be no doubt that Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben and others came from a place of paternalist contempt. My point is not that these brands are ahistorical objects without any freight to carry, but that most people don’t know, don’t care, and are re-inventing that context based on their own personal encounters with the brand, more than any kind of academic history lesson would provide.

I’ve heard it explained that “Aunt” in Jemima and the “Uncle” in Uncle Ben’s are diminutive forms of address for slaves, who were not addressed as Mrs./Mr. and this seems a plausible-if-not-good reason to modify the name, even if no one except specialist academics knew that fact. Still, I can’t escape the intuition that the issue is the depiction and that historical fact is a happy accident that proves the point. They could just rename it “Jemima’s” and keep the image. (You know, Jemima, from the agency.)

People under 45 might not recognize what I am referring to here because they have so many ready-made, hard-won images to choose from: The Princess Tianas, the Serena Williams’s, the Wakandas and Riri Williams’s. But for a long time–time I lived through–there were no Black faces to be seen anywhere, not until OJ and Michael Jordan. So seeing oneself–even as a painting, even as a cartoon–meant something. Do you know how deeply that burned in? Deep enough to make you weep the first time you see Hamilton.

This has, in a bizarrely retrograde historical moment, become overwrought, a kind of “You Go, Girl” overcompensation that feels tokenizing and inauthentic. We can’t merely have the iconography of Black people just living their lives. We have to protect them from being depicted as cartoons. And the solution, of course, is to erase them altogether.

So did I have some kind of sentimental feeling losing Aunt Jemima? No. I was just confused, like, didn’t we already deal with this? My sentimental favorite was the Cream of Wheat guy.

When my mom used to work late or take a trip and my dad was left in charge of dinner, he’d often make Cream of Wheat. And it’s ridiculous to say, but by the transitive properties of Kid Logic, I accordingly thought of Cream of Wheat as For Us By Us, being prepared by us. I mean, my mom didn’t make Cream of Wheat, and my father insisted he had learned from his father. Yes, the Cream of Wheat man was a Black man in a chef’s hat but so what? It was not apparent that he was anyone’s slave, or even anyone’s employee. He was just a chef. We have jobs, too. We are cooks, and chefs, and professors, and own agencies, and pass recipes down from Black father to Black son and that recipe is Cream of Wheat with Log Cabin syrup, no I don’t know if there was ever an actual cabin made of logs and further, I do not give a shit.

Being seen is important. It makes you real. You want to see yourself represented, looking back, not as mascot but neither as untarnishable token. Sometimes you just want the pleasure of being treated as normal, and being subject to the same as everyone else without it having to mean something. I make Cream of Wheat because I’m a chef. That’s all. Have some. Give it to your son. This is how we live. This is how we have always lived. The unseen oxygen of culture, invisible but always, always respirating, in and out.

Cream of Wheat is terrible, by the way.

There was some awkward moments in my house when we realized Stubbs, our favorite barbecue sauce, had a character, ‘Stubbs,’ on the cover. I HAD TO LOOK IT UP and verify that Stubbs was actually a real guy and his family was profiting off the sauce. We were safe, but what the hell? I liked Stubbs. I liked my idea of Stubbs. It was enough to me that Stubbs was some Black cowboy who sold the hell out of a recipe, but did it matter if he was real or not? I don’t think it did, I don’t think it does, I put that shit on everything.

I don’t like Marxist escapes of the Michael Brooksian mold, which is to say “this woke overreach is OK, not because you have the politics right but because big business is ultimately harmed.” I’m not interested in hurting anyone’s business, I’m trying to find syrup on a shelf.

I am feeling the inverse, though, which is, ‘a good side effect is that Black-owned businesses are becoming a preferred consumer choice.’ If this is what passes for victory, I’ll take it.

It’s just a memory that I had.